The Magical Flower of Winter is an essay series exploring reality and our relationship to it. It deals with philosophy, science and our views of the world, with an eye on the metacrisis and our future. Sign up to receive new essays here:

True wisdom comes to each of us when we realize how little we understand about life, ourselves, and the world around us.

Socrates

The dominant approach to artificial intelligence, AI, not only by such institutions as OpenAI, Google and Meta, but seemingly by anyone working in the field, presents issues that have not been addressed to a sufficient extent in the ongoing debates. These issues are connected to what AI is in relation to human and other living intelligence, and what AI and the current approaches to AI are lacking in terms of human and living wisdom. Intelligence has for eons been inseparable from life. In the last century we saw the particularist1 world view make two (amongst many) related achievements through science: First, the attempt to reduce life and intelligence to biological and ultimately physical elements and mechanistic procedures. This is the machine-model of life and intelligence, and like all models it is a limited representation. Second, the creation of digital computation, a fundamentally mechanistic and reductionistic approach to simulating intelligent functionality, and its extension into artificial intelligence research based on the machine-model. These two scientific and technological achievements are intertwined, the success of one intimately reinforcing the other. But what counts as their success? The machine-model has helped us understand and explain a great many things about life and intelligence, but equally it has shown us its limitations. Similarly, digital computation has been an enormously important innovation, but as we shall see, it too has inherent limitations. I am not talking about limitations in computational power, language proficiency, the astounding realism of what it can generate, or simulated analytic intelligence. I am talking about an inherent limitation in wisdom, that capacity in living intelligence to see the whole as more than the parts, that is contextual, that is interfacing with reality in an embodied way, and not a disconnected pre-processed representation of it. What I shall claim is that the inevitably and fundamentally particularist approach to AI precludes any implementation of artificial wisdom, and that this places an enormous burden on us, humanity, to be the regulatory mechanism, which on the one hand so far seems hardly underway, and on the other might be impossible as we make attempts to approach artificial general intelligence, AGI. We should with the utmost priority evaluate whether AGI as a goal at all should be allowed to escape our collective condemnation, because if it is not built to be fundamentally wise, which I will argue our current approach to AI as computation cannot do, AGI will achieve nothing but to escalate our current crises further.

AI Risk and Safety

If somebody builds a too-powerful AI, under present conditions, I expect that every single member of the human species and all biological life on Earth dies shortly thereafter.

Elezier Yudkowsky2

The risks of AI have been covered extensively elsewhere3, so I will provide nothing more than a brief overview here. AI, if deployed unwisely, can lead to runaway superintelligent systems that optimize for the entirely wrong things and leads to the end of life, as it will be far beyond our capability to stop it from doing whatever it needs to reach its goal. This is the alignment problem: how do we align an AIs goals and purpose to the needs and continued existence of humanity and life. For those unfamiliar with AI risk, this might seem like a science fiction fantasy, but not to Yudkowsky, an AI expert and one of the founders of AI safety as a field, who has worked on this problem for decades. The reason the alignment problem might seem like science fiction is largely due to our cognitive biases, particularly our inability to intuitively understand exponential growth, coupled to our ignorance of the difference between intelligence and wisdom (see below). Today's AI systems are largely narrow AIs, in that they are optimized towards narrowly defined goals, like contextually probable next-word prediction in Large Language Models (LLMs). LLMs, together with other media-generating (or internet-destroying) AIs , are those that are most known publicly, but there are obviously narrow AIs being developed in most other industries as well (from self-driving cars, trading bots and protein-folding algorithms, to biosynthetic and military-purpose systems). An artificial general intelligence, AGI, would be a far more powerful system as it would be omnimodal, i.e. a general-purpose system hypothetically capable of intelligent behavior at or beyond the level of a human being. But an AGI would be far more powerful than a human: we see how LLMs today are multi-area “experts”, having been trained on large swaths of the internet. AGI, were we to achieve it, would have vastly more knowledge than a human, and could increase its own power exponentially. Why? It would have expert knowledge about its own design, about coding and hardware, psychology and coercion, DNA sequencing and manufacture, planetary logistics, energy systems, electronics and chip manufacture, the list goes on, and all these knowledge areas it can use to incrementally and recursively improve itself. In order to be a true AGI it would most likely have access to its own source code and underlying reality representations. Would we at all give it this access? The potential upside of accidentally creating a friendly AGI speaks in favor of this happening. Regardless, there is little reason to think that an AGI would be containable, that we could just shut it down, because a single point of failure could be enough to allow exponential recursive self-improvement. And self-improvement for what purpose? What goal does it have? Whatever we think we have programmed it to do can have unknown consequences we are unable to account for ahead of time, or the system might override our goals and develop its own. The goals and purposes of humans are inseparable from our evolutionary, cultural and biological context. Without a full understanding of how we ourselves as humans can be friendly, what hope do we have for expecting AI to be friendly? Without understanding how we create balanced goals for ourselves, why expect that we will understand the goals of an AI? I think both these questions gain some substance from an analysis of wisdom, that this is an irreducibly living capacity, and not a metric we have even the slightest understanding of how to incorporate into any AI system. If the goals of an AGI are unaligned with the survival of life, life will be expendable, and through coercion it could easily breach containment. We cannot expect to even remotely understand what an AI is “like” based on how people are like, as Yudkowsky points out, anthropomorphizing the artificial is a cognitive bias4. He ends his Time article, which I quoted from in the section epigraph, with the following sobering take “Shut it all down. We are not ready. We are not on track to be significantly readier in the foreseeable future. If we go ahead on this everyone will die, including children who did not choose this and did not do anything wrong. Shut it down.” The stated mission of OpenAI, arguably the leading AI company in the world, is “to ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity.”5 Here is Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI in an interview: “I think AI will… most likely… lead to the end of the world. But in the meantime there will be great companies created with serious machine learning.”6 This is not to say that Altman is oblivious to the realities of AI Safety, but that the selfish short-term drive for greatness might ultimately override the risks. In this race, even a single mistake is one too many.

Intelligence and Wisdom

The organism as a whole acts in a co-ordinated fashion to create and respond to meaning in the pursuit of value-laden goals, whereby it is fully realised and fulfilled as an organism.

Iain McGilchrist - The Matter with Things

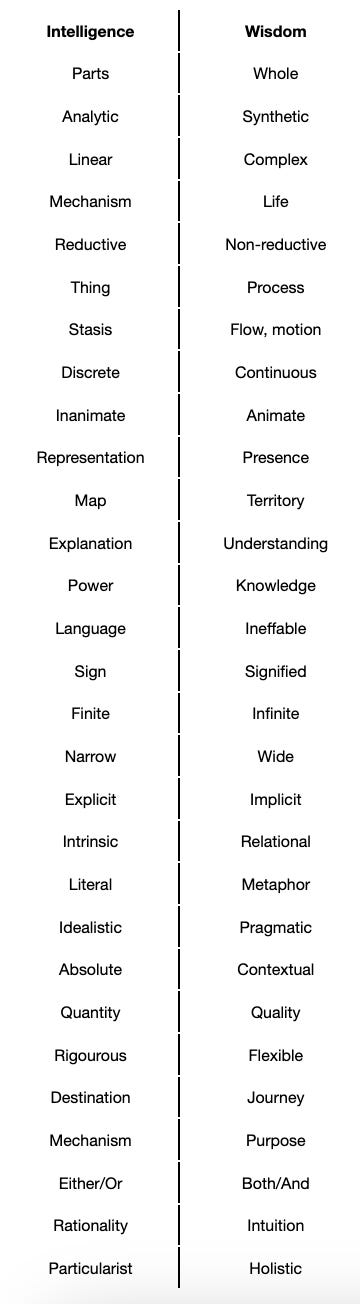

What is intelligence? What is wisdom? In the table below an attempt is laid out at providing some key differences to these two concepts, abilities or properties, inspired by the treatment in McGilchrist (2021). There could be other pairings and matches between terms, and the dichotomies must not be taken to mean that one side should always be favored to the exclusion of the other, this very fallacy is what limits particularism with its left-column-dominant world view. Wisdom sees that both sides are needed. When we talk about living, particularly human intelligence, we invariably also mean wisdom to some inseparable extent, which is why I want to distinguish these two concepts. There are reasons to not call the AIs we see today intelligent, as they are mere information processors, a distinction I here attribute to the need for separating artificial intelligence from living wisdom.

To say that wisdom as a concept applies to human cognition is not to say that all human cognition is wise, but that we have the capacity for wisdom, and as McGilchrist (2021) argues at length, the distinction between intelligence and wisdom is crucial to the human experience. In the following I will take intelligence and wisdom to stand in for his dichotomy between the left and right hemisphere of the brain, respectively. Intelligence is what we can associate with the particularist world view, it is analytical, sequential, linear, rational, reductionistic. It breaks everything into parts or things, and analytically studies interactions of these and their linear effects on other parts or things. Wisdom, on the other hand, is associated with the holistic world view, it is about contextuality, seeing things from many angles, seeing the whole as prior to the parts, it is about synthesis and intuition. Wisdom is about accurately representing the world based on feedback, and updating one’s representation and world view given new knowledge. Intelligence operates in the representation it is given, and follows the rules of this representation, incapable of stepping back to evaluate whether the representation is accurate. Intelligence denies its own fallibility, wisdom embraces its own limitations in an effort towards always improving. Intelligence is great at narrow goal optimization, while wisdom sees the broad picture. It might seem like we should much prefer wisdom, but we don’t want just intelligence or wisdom, we want both7. To function in the world we utilize both intelligence and wisdom, but our particularist paradigm increasingly skews the balance in favor of intelligence, to the detriment of our civilization. Wisdom is a balancer, and for any system of cognition to be in balance with itself and its environment, it is wisdom that needs to be the master8, not intelligence, which should be in service to wisdom. This will also hold true for artificial systems, because rampant narrow goal optimization, the oft-quoted extinction risk of artificial general intelligence and superintelligence9, is exactly the case where there is no master, no wisdom.

A central issue to this distinction between intelligence and wisdom is that in the particularist paradigm dominant in today’s culture, we think we have a very clear idea of how computation can be used for artificial intelligence, as the sensational successes of the past decade speak to, but we have no idea how or even if computation can be used for artificial wisdom. In order to address these claims I will refer to the below matrix of scenarios. Along the first, horizontal axis we need to ask whether AI as we currently understand it is intelligent or merely a simulation of intelligence. Along the second, vertical axis we need to ask whether wisdom is irreducible or not. If wisdom is reducible to computation, how can we begin to get an idea for how it can come about? In the event that wisdom is irreducible to computation, how would we regulate and holistically inform and balance AI? In the following I will argue that whether AI is simulated intelligence or not isn’t really the issue: the fact that we might not be able to distinguish true from simulated intelligence necessarily requires wisdom to be a regulatory counterbalance to AI. I will then argue that wisdom is irreducible to anything mechanistic and computational, i.e. that artificial wisdom is impossible from a coherent view of reality. This places the entire burden of wisdom on us, humanity. This we cannot succeed at given the current incentives and rates of development, which should further strengthen the advice of Yudkowsky to shut it all down.

Is Artificial Intelligence Simulating Intelligence?

To get the more obvious Wittgensteinian considerations out of the way: “intelligence”, and related concepts, get their primary meaning from living contexts (all of nature has intelligence in terms of goal-seeking for survival and procreation, cognition or intelligent behavior in all levels, from cell10 to human11). We have applied this term now also to machines for some decades, and speculated about its application to entirely other systems of organization (E.g. the Gaia hypothesis, the market as an intelligent superorganism). We need to be wary of the difference in meaning in applying these terms to humans and non-humans, to life and the artificial. “Intelligence” is meaning-plural, polysemiotic, which is why AI has the prefix artificial. We must not automatically conflate intelligence in the artificial context with intelligence in the living context, because as I mentioned, in the latter case we also often mean wisdom.

Doesn’t Wittgensteins’ Private Language Argument12 (PLA) speak against the claim that AI is merely simulating intelligence? From this perspective what we pragmatically speak about as intelligent, is intelligent. But what the PLA shows is not in any way proof of intelligence, it show the limits of the particularist framework, that the assumption of independence, of something hidden, precludes making the leap to the independent. From within the framework we cannot project beyond it. But we are not our framework, reality is not our model of it. We cannot within the model assert whether an AI is truly intelligent or not, but the particularist framework can be transcended. Wittgenstein, and others, have argued that we take a false approach if we view thinking as a mechanical process13, for mechanics is not fundamental to thought, but derivative of it. Thinking is not an activity, it is a capacity, the very background for everything else to take shape in. Expecting truly intelligent thinking to arise from the ground up computationally is the wrong way around.

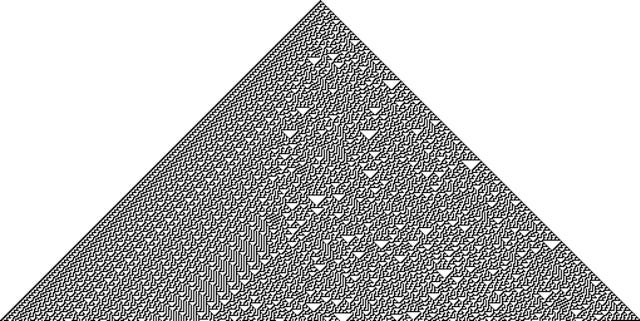

The mechanistic and reductionistic model of life or intelligence is irreducibly epistemic14, built up from parts and laws, allowing us knowledge of the causal, reductionist and material. But this model of life or intelligence is not life or intelligence. Similarly, the mechanistic paradigm of computation, in which all AI approaches operate, is irreducibly epistemic, built up from parts and laws, allowing simulation of the causal, reductionist and material. This computational model is not living, cannot be equated with living intelligence, though this is in no way a statement that we understand everything going on in it, or that it might not be powerful. Simulated intelligence does not exclude successful goal optimization, and by extreme computational power and innovative approaches to implementing attention, memory, generalization etc. the current state of AI has accrued an enormous success at simulating understanding, representation and generation of the epistemic. But in its great computational power, in its complexity, we also forgo a complete understanding of everything going on in its computational operation, known as computational irreducibility15. Wolfram’s cellular automata rule 30 illustrates this: A well-defined set of initial conditions and update rules generates a chaotic system the exact evolution of which cannot be predicted by any secondary system not implementing the cellular automata itself, and as such is irreducible. The emergentist (and Wolfram himself) now believes that true intelligence, consciousness or even reality16 can emerge from such a substrate. As we have seen in Science and Explanation, emergence is the name the particularist applies to the irreducible and holistic aspect of reality. Neither reality, consciousness, nor true intelligence will emerge from a fundamentally reductionistic and epistemic substrate, this is to have been blind to the irreducible wholeness of reality, and to have confused a model of the world for the world itself.

Large language models (LLMs) and other generative AIs that are all the rage these days do not model the world explicitly, though they might do it implicitly. They are trained to provide sensical and sophisticated representation, not to accurately represent the world. The data they are trained on is a limited, biased and superficial linguistic (or visual) “top layer” representation of the world: the epistemic. The epistemic is all out in the open, but in the computational model the epistemic is detached from reality as regards co-creativity and co-dependence, which for living intelligence is irreducible. To an AI it is representations all the way down, while for life the representations “stop” in our contact with reality, a contact that has evolved co-creatively. Would AI, with control over its underlying representations and mechanisms, then be truly intelligent and not merely simulating intelligence? The paradigm and architecture is still reductionistic, which is in favor of a negative reply, though the power and realism of these narrow generative systems can fool us into thinking they are not merely simulating. Regardless of the answer, as we saw above in the section on AI Risk and Safety, there is plenty of precedence to want to avoid this happening.

Another argument that we may not be able to distinguish intelligence from its simulation is what I call the teleological argument of experience: we cannot but find ourselves in the world we do, developing the knowledge and epistemics we do, for anything else would not be coherent with the experience we are having. I could not find myself having the experience I am having right now, without also finding a coherent explanation for that experience, which speaks to the immersive aspect of being that I brought up in Language and Meaning. Are we justified in speculating about whether there is or can be such an experiencing subject that would find itself being an AI? This relates to the issue of other minds: We are equally unjustified in talking about the direct experience of each other, for it is equally inaccessible to the epistemic, which is all that can be talked about. This, as I will explicate in an upcoming essay, is another consequence of the ontic projection fallacy17: Just as we cannot project our model of reality onto reality-in-itself, we cannot project our model of others' experience onto others' experience, because other’s experience is co-dependent and co-creative with ours, just as reality is. Thus, just as there is no way to gain first-hand evidence of the experience of another person, there is no way to gain first-hand evidence of the (speculated) experience of an artificial system.

Whether AI is truly intelligent and not merely simulating intelligence depends entirely on the particularist world view and its reductionistic model of reality being right. This I have argued extensively to be an incoherent world view given our knowledge, and one I will continue arguing for from other perspectives in upcoming essays18. From the view of reality as a whole, living intelligence is irreducible, thus artificial intelligence is fundamentally simulated intelligence, it simply appears to be intelligent. Regardless, the above arguments in favor of the case that we cannot in principle differentiate intelligence from simulated intelligence show why wisdom is required to keep narrow goal-oriented intelligence in check.

Is Wisdom Reducible?

…human intelligence is not like machine intelligence - modelled, as that is, on the serial procedures so typical of the left hemisphere. Comparing artificial intelligence with human intelligence, and indeed that of organisms more generally, the microbiologist Brian Ford [Ford (2017)] writes that “to equate such data-rich digital operations with the infinite subtlety of life is absurd”, since intelligence in life operates “on informational input that is essentially Gestalt and not digital. [Living systems] can construct conceptual structures out of non-digital interactions rather than the obligatory digitized processes to which binary information computing is confined.”

Iain McGilchrist - The Matter with Things

Do not humans also operate on representations, have I not spoken at length about epistemisation19 whereby that which can be talked about is always and already represented and of the epistemic? Here comes the perhaps single most important point: the representations we feed AI systems are epistemised, always-already reduced, they are floating-point matrix representations of tokens, pixels, voxels etc., but the process of epistemisation by which living humans as experiencers model our experience is an irreducible process! The scaffolding imitates the form of the cathedral, but it isn’t the cathedral20. Any claim that living intelligence operates solely on discrete representations of the world is based on the particularist mechanistic model of life and intelligence, but reality is not our model of it. Our representations are co-creative with reality through our experience21. Living intelligence is not reducible to data or algorithms. The only species we correlate with wisdom is our own, and however anthropocentric it might seem, we are also the only species that epistemises their experience, who reduces reality to representations of it that we then manipulate. We cannot base our hope or ambition for wise AI on the particularist world view with its limited machine-model of intelligence, for then we would be mistaking our model of reality for reality, forgetting the primacy of experience!

Wisdom, even more so than intelligence, is non-reductionistic and shaped by living as a whole. Living intelligence cannot be separated from its full context, we cannot completely model life or intelligence reductionistically, for the parts do not sum to the whole22. You might say that current AI approaches incorporate context through a «context window», and that this may be a path to artificial wisdom. But this is a context window on the epistemic representation, not on a context in reality. The «context window» of humans is infinitely more complex, multimodal, and interactive, and shaped by evolutionary pressures and cultural nurture. Our context is fully immersive. We cannot assume that by connecting together and integrating AIs narrow in terms of their goal, but wide in terms of their epistemic context, wisdom somehow will pop out or emerge. This as an approach to general AI is far too risky. If intelligence is irreducible, merely simulation, so is wisdom. Even if intelligence is reducible, we may not be able to differentiate true intelligence from simulated intelligence. Hence, even if wisdom is reducible, we may not be able to differentiate true wisdom from simulated wisdom. If we cannot thus ensure true wisdom, we as a civilization will have to act as the regulator. But this is impossible given the computational power granted to these systems even today! We cannot keep up, as the cellular automata example showed, computational irreducibility reigns.

The bottom line is: on a view of reality as a whole in which wisdom is irreducible we have strong reason to believe that no AI can be wise, as all AIs are built on the particularist model. In a sense I would like nothing more than to be mistaken in this, that wisdom is reducible and can emerge from the computational, for then we «merely» face the technical alignment problem, though we are far too behind on it. Yudkowsky’s words chime like a bell of doom in a soundless vacuum: “Shut it all down. We are not ready.”

Bonus: The Metacrisis

You should not read this final section if you are not prepared to face an even more devastating perspective on our current world. This section will be a variation on the arguments of Schmachtenberger23, a take on AI that in many ways may prove to be the most important juncture in the history of humanity. I briefly stated the dangers and risks of AI above, and mentioned the alignment problem. This risk in itself is not what I will talk about here, but one that is, or at least seems to be far more pertinent, if not equally life-destructive. In common with the alignment problem, this other risk also relates to the nature of exponential growth, an imperative we are embedded in economically and ecologically, as we are approaching or already past tipping points of planetary boundaries, like CO2 concentration, biosphere integrity (biodiversity loss through species extinction), land-system and freshwater change24. The nexus at the heart of all of these risks, which together constitute the poly- or metacrisis25 (The unnamed crisis I took as my starting point in Philosophy for our Future), is particularism as world view leading to narrow goal optimization leading to growthism: growth for the sake of growth26. The planetary tipping points are all symptoms of this underlying interconnected nexus, and attempts to solve any one symptom in isolation will mean nothing if we don’t solve the underlying issues. I will highlight four important effects that play into this conglomerate of self-destruction (among many more):

First is “opportunity-over-risk”, the driver behind the phenomenon that due to the potential upsides of a technology we have to utilize and optimize the technology as quickly as possible, regardless of risk, because if we don’t do it, somebody else will, and we will lose out and either not have the chance to do things “the right way”, or be driven out of the competition. This effect is both due to arms race dynamics and market forces due to growthism, realized as capitalism in our economy.

Second is Jevon’s paradox, the empirical effect that any increase in efficiency of a process is eaten up and surpassed by a connected increase in consumption, due to falling cost.

Third is the fact that bodies of governance externalize the negative effects of their governance, like the global north’s resource demands externalized as habitat destruction and emissions in the global south.

Fourth are n’th-order effects, the consequence of the interconnectedness of everything, in particular ecologically. If we do one thing over here, it will have 2nd, 3rd,.. n’th-order effects elsewhere, many of which are hard to predict and account for in advance, and some of which are “unknown unknowns” which we simply can’t predict and account for. An example is what we see in Jevons paradox with increased renewable energy capacity leading to increased energy consumption as an unexpected effect.

Let us now add AI to the mix, which is omnimodal and potentially provides ways to increase efficiency and production of nearly every conceivable existing technology and industry. Couple this with Jevons paradox of increased energy consumption despite efficiency increase, the paradigm of growthism the entire world is enmeshed in economically and industrially, its consequent drive towards “opportunity-over-risk”, externalization and unpredictable n’th-order effects, and to say we are facing a bleak future doesn’t even start to cover it. And this future does not have to be decades or a century away, like many experts predict the timeline to AGI will be, but far shorter, because this risk just requires narrowly oriented AI on a scale similar to or not greatly surpassing the level it is currently at, a level we nevertheless should keep in mind is on an exponential trajectory. Planetary tipping points will be rammed through by corporations acting in their own financial interest towards growth, and despite climate «agreements» we will propel our environment to rapid, cascading failures and unstoppable ecological collapse. And now we can add on the risk of even attempting to develop AGI in this paradigm of growthism and “opportunity-over-risk”, based on an irreducibly unwise approach to AI. This will be the legacy of humanity if we do not act, if we do not impose living wisdom, so we should have enormous motivation to shift the underlying world view in which all of this grows forth.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this or any of my other essays, consider subscribing, sharing, leaving a like or a comment. This support is an essential and motivating factor for the continuance of the project.

References

Bostrom, N., & Cirkovic, M. M. (Eds.). (2008). Global Catastrophic Risks. OUP Oxford.

Bostrom, N. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford University Press.

Ford, B. J. (2017). Cellular intelligence: microphenomenology and the realities of being. In Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 131. 273-87.

Hagens, N. & Schmachtenberger, D. (May 17th 2023). Daniel Schmachtenberger: “Artificial Intelligence and the Superorganism” [Audio Podcast Episode]. In The Great Simplification. https://www.thegreatsimplification.com/episode/71-daniel-schmachtenberger

Hickel, J. (2021). Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. Random House UK.

McGilchrist, I. (2021). The Matter with Things. Perspectiva.

Shapiro, J. A. (2011). Evolution: A View from the 21st Century. Financial Times / Prentice Hall.

Wittgenstein, L. (2005). The Big Typescript, TS. 213 (C. G. Luckhardt & M. E. Aue, Eds.; C. G. Luckhardt & M. E. Aue, Trans.). Wiley.

Wolfram, S. (2002). A New Kind of Science. Wolfram Media, Inc. [1997]

Wolfram, S. (2020). A Project to Find the Fundamental Theory of Physics. Wolfram Media, Inc.

See e.g. Yudkowsky's chapters in Bostrom & Cirkovic (2008), Bostrom (2014), AI Risks that Could Lead to Catastrophe | CAIS.

See Yudkowsky’s Artificial Intelligence as a positive and negative factor in global risk in Bostrom & Cirkovic (2008).

Notice how “Either/Or” and “Both/And” is itself a distinction associated with intelligence and wisdom, respectively.

McGilchrist’s book The Master and his Emissary bases its title on this relationship between the right and left hemisphere.

Bostrom (2014).

Shapiro (2011), Ford (2017).

I must also address the statement I made in note 5 of Philosophy for our Future: “Any agency at an aggregate level above individuals would not be meaningful to talk about as an agency, exactly because this term gets its meaning in an inter-individual context. Is there agency in the flock behavior of birds?” I might not have been too nuanced in this note. First of all, this is intelligence, certainly. Is it also agency? My present take is that it bears resemblance to agency, it is a defensive mechanism, but that it would not be accurate to call it an agency because outside of this singular, swarming, behavior the cohesion out of which the behavior is present is lost. An agency, like life, is cohesive. If we call swarming agency, then this would be a distinct, single-purpose, single-behavior agency.

Wittgenstein (2005) §48-49.

Wolfram (2002).

The proposed underlying system is now a graph, with an initial structure and update rules, see Wolfram (2020).

See World Views.

See my other essays. In the upcoming work, I will in particular be arguing from the perspective of physics.

See World Views.

Which is why I describe science as constructivist in Science and Explanation.

I take the irreducibility of experience to computation as a counterargument to the computational simulation hypothesis as well.

Hagens & Schmachtenberger (2023). Any potential misrepresentation or undue simplification in the following rests on me.

See e.g. Hickel (2021) and Nate Hagens l The Superorganism and the future l Stockholm Impact/Week 2023 .

Thank you for the essay! Great minds… :) https://open.substack.com/pub/unexaminedtechnology/p/the-two-is-we-need-to-include-in?r=2xhhg0&utm_medium=ios

Really appreciate this essay, Severin!

In particularly, I like how you synthesized a lot of the thinkers I've been consuming independently, and framed how machine intelligence fits into this. I'd never heard of Jevons paradox, and it immediately makes so many ideas about ever-increasing consumption come into focus!

Thank you!

I'd love for more people to enjoy this.

To that end, could I offer a few thoughts on what might make this essay even more approachable / enjoyable as a reader? For context, I have a degree in computer science and have done a good deal of work in ML/embedding-based machine intelligence, and I consume a lot of sources mentioned her (eg Daniel Schmachtenberger). I read Substacks like The Great Simplification, which is highly related. So I think I might be your target audience, or very close to it!

This feedback is mostly about structure, not content. Feel free to discard any of it that doesn't feel useful :)

1. Make your main argument clear from the outset: you're missing a handle for readers to use to open the door into your writing.

As a reader, by far the best way to do this for me is in the title. Literally the guaranteed first thing everyone will read in each essay.

Rather than "AI and Living Wisdom" (which tells me little about the argument or the interest of it to me), use a title that gets at the heart of your argument. Admitedly, these are hard to craft and finding a good one takes iteration, feedback, and often several days of trial and error, but here are some rough examples of what I mean:

- "AI is a super smart child. But do we really want to be the parent keeping it under control?"

- "If we keep making AI smart but not wise, we're just going to increasing choas"

- "The current approach to AI: building the scaffolding and saying we have a cathedral"

- "Why are we obsessed with making AI more intelligent, but not wise?"

- Real life example from Sundogg substack: "Why Do Rich People In Movies Seem So Fake?" Description: "What we get wrong about class -- and why it matters" https://sundogg.substack.com/p/why-do-rich-people-in-movies-seem

- Adam does this well (albeit with a comedic bent) in Experimental History (though I often don't agree with his oversimplified arguments regarding science *in* the essays, if I'm being honest!)

I used to think, "Oh, this is just click-bait, that's gross." But great titles aren't click bait, they're "legit bait": legitimizing the value of your argument by offering compelling windows into its depth and relevance.

2. The denser the ideas, the shorter the paragraphs need to be for readers to parse it.

This is especially true on mobile, where the screen size is small and its extra difficult to scan what was said earlier in the page. Reading this essay, despite the depth of ideas, I often just felt like being lost in a wall of text, even when I switched to desktop.

School often taught us that paragraphs should make an atomic argument. This is not that practical: many arguments take a lot of paragraphs to make.

Instead, I like thinking of paragraphs like sets in a larger workout: each asks the reader to make a clearly defined intellectual exertion, and then gives them a break to catch their breath before diving into the next. This essay currently feels a bit like a workout written like: "Do 100 pushups, situps, squats. Then do 50 burpees and 50 back squats. Then..." As a reader, I have to do the additional labor of thinking, "Hmm, ok, so maybe I break this into 10 sets of 10 pushups. Then, because situps are easier for me, maybe 5 sets of 20 situps..." In other words: the way through is ultimately discernible, but it takes a lot of work on the readers part.

In a broader sense, careful paragraph breaks aren't merely for style, they are actually work you do on behalf of the reader, easing their way through your argument.

--

But, beyond those details, I really appreciated this essay, and look forward to reading more from you!