The Metacrisis - Analysis

A provisional analysis of the metacrisis through the lens of traps, world views and limited designs.

This essay is part of the second phase of The Magical Flower of Winter, a project that now turns its focus from outlining a metamodern view of reality as a whole, towards the metacrisis. The thread that links these two phases is how the former can be considered an attempt at providing a world view that may better help us deal with the latter. The first phase can best be accessed through its introduction:

Sign up to support the project and receive new essays here:

— Oh Mother! Why have you left us? It is so dark and we cannot see.

— Dear child. Come so. Come here. Do you not see that it was always this dark? What made you think that what you were doing was seeing in the first place? You think it is dark because you contrast it to a light of your own making, a light that now is fading. This is no tragedy, though it takes a while to get used to. You await signs that tell you to change your ways, but ignore them when they are shown to you. Open your eyes!

— Oh.. things are so hard! Life is hard! The world shifts beneath our feet and we keep falling down! It hurts! What are we to do? Make it stop!

— Poor, poor child. Hard or easy, life cares not. In a way, all one can do is fall! Falling, you rise. What you do now is forge a new flame, but this time in secret. A low flame, a flickering flame, a flame fed by the dark, and not by your dreaming. This way the flame won’t fade as the dark envelops it. This way you won’t fall by the world’s shifting.

In the previous essay I viewed the first phase of this project through the lens of metamodernism, tracing parts of its development as a world view, and showcasing elements of this world view in terms of philosophy, metaphysics, narrative, critique and how it may provide a return to meaning and value. Braided through this account was a diagnosis of the metacrisis as at least in part bound up with the progress narrative of modernity, and that to gain the capacity to deal with this nexus of crises we have to change a great deal about how we relate to the world. Such a change in world view is precisely what this project aims to contribute to. In this essay I aim to go further in breaking down the elements of the metacrisis by identifying how cognitive and multipolar traps relate to our world views and limited designs, and how these factors act to reinforce each other, locking us in beliefs and behaviors at odds with the reality we face.

In breaking down the metacrisis, attention must be paid to the limits of such efforts of reduction. The metacrisis is a nexus of vast complexity and any analysis will be unable to envelop it without loss. These are crises that are societal, socioeconomic, political, spiritual, ecological, epistemological and so much more, and any conceptual treatment of them can only touch on parts of this territory. Even with these provisions set down, we can still improve our understanding by analysis, as long as this analysis is seen in the context of its own limitations and assumptions.

Characterizing the Metacrisis

The ways of characterizing the metacrisis are many. Economically and societally, the metacrisis pertains to growth, how growth is coupled to energy, and how energy is coupled to resource extraction. There is no growth in profit that is not ultimately coupled to some form of extraction.1 Agriculturally, the metacrisis pertains to the many challenges we face because of the externalities, the side effects, of industrial farming worldwide and the vulnerability of the agricultural system to changes, be they of the climate or otherwise.2 Ecologically, there are the planetary boundaries, nine of which are identified as critical to the well-being of earth, of which climate change is only one. We are overshooting all but three of these.

Educationally, the default is a system of standardized teaching made to produce high test scores. This system is now competing with the profit-maximizing agendas of social media and AI algorithms for the educational and non-educational attention of our children and students.3 Culturally we are at war, but it is not really a war of opinions or cultures, but of who can win at mediating these algorithmically on social media. We are fed ever worse, ever more hollow and profit-driven consumer products and entertainment in part as a distraction from the state of the world. At the same time the world’s complexity and, at times, hopelessness drives us right to them. And at the forefront all of this we have an advertising industry itself bent on squeezing every last grain of attention out of us for profit, if not outright attempting to manipulate us into behaviors in service of political outcomes and consumption.

Technologically we suffer from externality and context blindness, that sacrifices ecological and human well-being for narrow and short-term growth ambitions, in a climate of limited coordination and regulatory scarcity. Geopolitically, the lack of planetary mandates prevent global concerns that affect us all to be cared for properly. We suffer the lack of a corresponding wisdom that planetary powers require for their stewardship. Spiritually we suffer the aftermath of secularization, modernity and postmodernity, tendencies of world view devoid of meaning and purpose because we believe these to have been reduced or relativized away, and one where our relation to each other and Nature is one of separation and independence, where any notion of the sacred is nonexistent. This being only a world view is transparent to us.

Politically the luckiest of us suffer forms of democracy subject to the interests of the highest bidders, and as voters we are presented with a slim and polarizing menu of choices rather than the full range of possibility corresponding to the plurality of political opinion.4 Much of our lives is spent in servitude, willingly or not, to the techno-industrial powers of quantity and optimization, blind to quality and human values. All of these challenges interconnect, all of them arising from dynamics that relate to how we view our world, and how we base our interactions and designs on this view. In this essay I hope to shed some light on this interconnection.

One central aspect, evident from the above, is the issue of growthism, the seeking of growth for the sake of growth. Growthism exemplifies how we are trapped in enterprises where we throw wisdom and well-being out the window for short-term and narrow goals, our limited designs. If we don’t sacrifice our values for profit, someone else will, and we can’t afford that if we want to stay in the game. At least in part, our limited designs arise out of a skewed world view. Jonathan Rowson, in Prefixing the World, characterizes the metacrisis in the following way:

The metacrisis is the historically specific threat to truth, beauty, and goodness caused by our persistent misunderstanding, misvaluing, and misappropriating of reality. The metacrisis is the crisis within and between all the world’s major crises, a root cause that is at once singular and plural, a multi-faceted delusion arising from the spiritual and material exhaustion of modernity that permeates the world’s interrelated challenges and manifests institutionally and culturally to the detriment of life on earth.

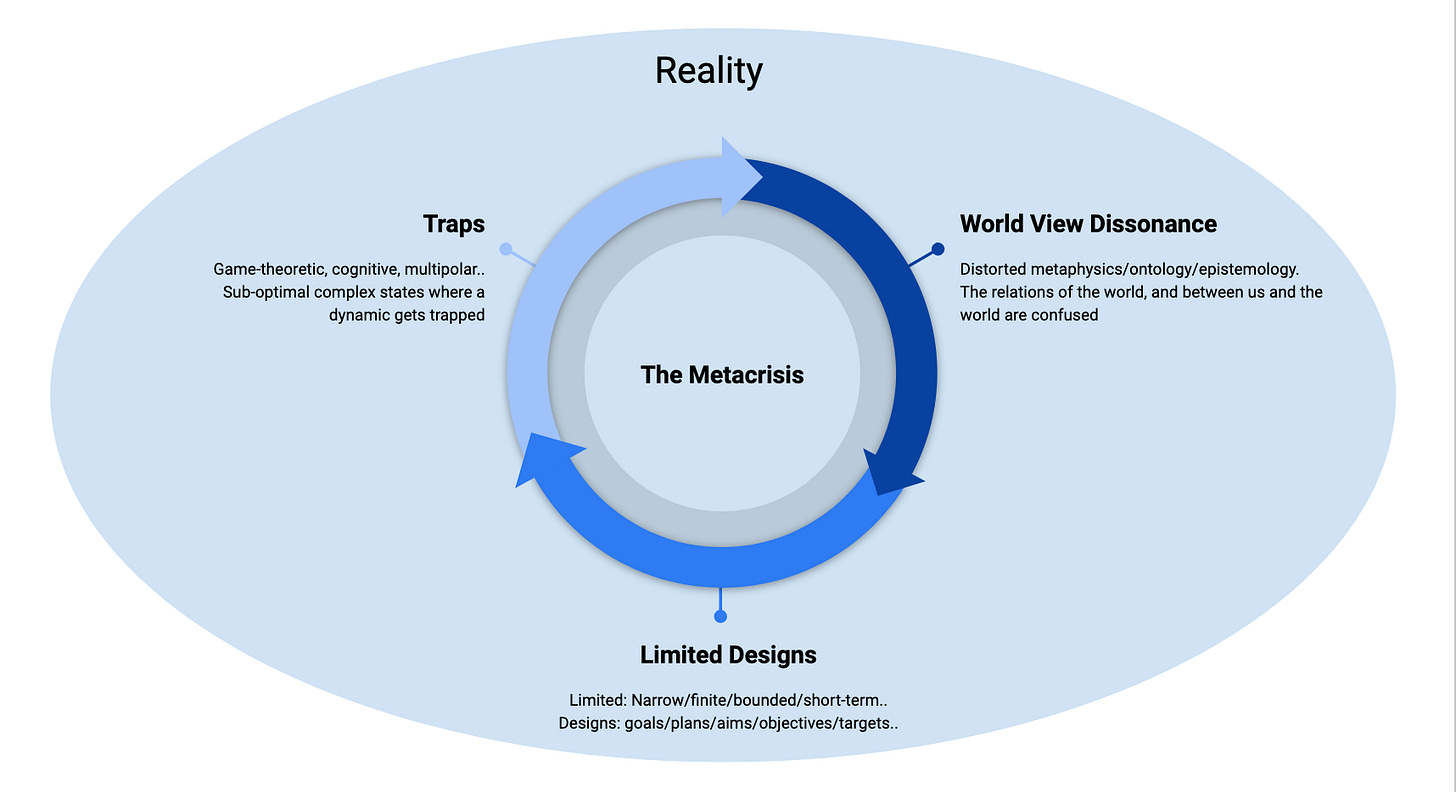

As such, this multi-faceted delusion in our world view is another central facet of the metacrisis. These are three interconnected components of the metacrisis I will try to bring into contact later in this essay: our world views, limited designs and traps. Before doing so, some comments on contextuality and technology.

The Contextuality of Technology

Sometimes it is better for certain secrets to remain veiled by arcane words. The secrets of nature are not transmitted on skins of goat or sheep. Aristotle says in the book of secrets that communicating too many arcana of nature and art breaks a celestial seal and many evils can ensue. Which does not mean that secrets must not be revealed, but that the learned must decide when and how.

Umberto Eco - The Name of the Rose

Important to any holistic analysis of the effects of technology on society is the realization that nothing can be considered in isolation. The context of the technology in question has to be considered in full, and the context of a technology very much includes how it is used and for what goals.5 This immediately dashes any notion of technology as value-neutral, as how and for what are value-oriented enterprises. Any innovation or technology, any creative process, is part of a larger context of culture, socioeconomics and politics, and will be shaped by the conflicts or imbalances inherent to these.

One could claim that the creation of the atomic bomb was a universally bad process, that an atomic bomb has no good uses, but this would be a projection outside the bounds of context. Atomic bombs would be considered useful in destroying asteroids on collision course with the earth, and many would deem this a good use of them if it stopped the destruction of the earth. Similarly, if people could somehow trust each other at scale and be united in the sacredness of life and the earth, a world with atomic weapons would first of all likely never have come to be, but it would also be a world without the pressure of mutual destruction. These are of course wildly speculative scenarios, but they go to show that a technology or creation cannot be considered outside its context, a context that is shaped by utility, pragmatics, culture, history, conflict, and so on. To view a thing on its own is only useful or appropriate in very specific cases.

Social media technology could be good and useful for humanity, but not when they arise as part of a growth-driven economy. As we will see, the paradigm of growth makes us throw the aspects and drivers of the technology that would make it good or useful under the bus. At the behest of profit-capture, aspects aimed at human well-being are sacrificed for aspects aimed at attention capture, addiction, misinformational warfare and behavioral manipulation.6 Technologies aimed at aiding the green energy transition could be good and useful for humanity, but embedded in the economic growth trap, these have only contributed to an energy addition to fossil fuels, not a replacement. Agricultural innovations could have led to food prosperity for all humans and humane animal husbandry, but installed in a context of growth they have led to biodiversity loss, soil degradation and inhuman industrial farms. Innovations in manufacturing could have been used to cut down our resource needs, but are instead used in service of increasing them.7 Marketing and advertising innovations could have been used to forge mutual respect, appreciation of beauty and art, an understanding of our dependence on each other and the earth, but these values are instead renounced in favor of promoting consumption, unhealthy ideals, and distractions from what makes life worth living. Economic innovations could have led us out of the growth trap, but have instead largely been marshalled towards digging the hole we are stuck in deeper. Suffusing all of these choices is our inability to not do a thing when this would benefit us long-term, a lack of design that extends beyond the immediate. This is no wonder when we are trapped in a dynamic that disincentivizes wisdom, as we will see.

The Consilience Project summarizes their take on the value non-neutrality of technology by listing five propositions towards axiological, value-directed, design:

Technology is created in pursuit of values, and results in the creation and transformation of values.

Technology requires the creation of more and different technology; multiple new technologies evolve together as functionally bound sets, forming evolving ecologies of technologies.

Technology shapes our bodies and movements as a human-created habitat, and thus is deeply habit forming, both for individuals and societies.

Technology changes the nature of power dynamics in unpredictable ways, creating an environment that advantages some humans over others, setting up selection pressures that force personal adaptation to and adoption of new technologies.

Technology impacts the kinds of ideas we value, the quality of attention we pay, and our conceptions of self and world.

Technology, what we create, are extensions of our capabilities, be they physical or intellectual. These work in tandem with the values we manifest in shaping the world around us. Importantly, this shaping is both direct and indirect, as technologies not only shape the physical world, but also our view of it, and with this, our values. We view the past through the lens of our present world view, a lens that has been shaped by the context that has brought us to the present. Thus, we cannot clearly see the path we have taken, because the origin we moved from is distorted by the lens we look back on it with. Because technology is part of this context, and because technology in many ways is in service of growth-driven incentives that sacrifices wisdom, this causes another kind of trap wherein we lock ourselves in patterns of activity and thinking that through normalization reinforces unwise processes, the very same processes that are incentivized to propagate for reasons perpendicular to human well-being. In other words, we are led to world views that blind us to their negative externalities, by processes whose interest it is to veil that this is even occuring. To understand this in more detail, we now turn to the nexus of the metacrisis.

Breaking Down the Metacrisis

The dynamic I claim underlie and drive many aspects of the metacrisis has been touched upon in parts by Scott Alexander, as well as in the work of Daniel Schmachtenberger (as made available in large part through conversations, e.g. with Nate Hagens). In the following I attempt to summarize and generalize their work a bit further, and in particular I try to establish the role of world views and limited designs.

Multipolar Traps

A multipolar trap is a multi-player version of the “prisoner’s dilemma”, the game-theoretic situation where two people acting in their own best interest are best served by betraying each other rather than cooperating, even when cooperation has a higher payoff. The multi-player version is concisely illustrated in Scott Alexander’s Meditations on Moloch:

As a thought experiment, let’s consider aquaculture (fish farming) in a lake. Imagine a lake with a thousand identical fish farms owned by a thousand competing companies. Each fish farm earns a profit of $1000/month. For a while, all is well.

But each fish farm produces waste, which fouls the water in the lake. Let’s say each fish farm produces enough pollution to lower productivity in the lake by $1/month.

A thousand fish farms produce enough waste to lower productivity by $1000/month, meaning none of the fish farms are making any money. Capitalism to the rescue: someone invents a complex filtering system that removes waste products. It costs $300/month to operate. All fish farms voluntarily install it, the pollution ends, and the fish farms are now making a profit of $700/month – still a respectable sum.

But one farmer (let’s call him Steve) gets tired of spending the money to operate his filter. Now one fish farm worth of waste is polluting the lake, lowering productivity by $1. Steve earns $999 profit, and everyone else earns $699 profit.

Everyone else sees Steve is much more profitable than they are, because he’s not spending the maintenance costs on his filter. They disconnect their filters too.

Once four hundred people disconnect their filters, Steve is earning $600/month – less than he would be if he and everyone else had kept their filters on! And the poor virtuous filter users are only making $300. Steve goes around to everyone, saying “Wait! We all need to make a voluntary pact to use filters! Otherwise, everyone’s productivity goes down.”

Everyone agrees with him, and they all sign the Filter Pact, except one person who is sort of a jerk. Let’s call him Mike. Now everyone is back using filters again, except Mike. Mike earns $999/month, and everyone else earns $699/month. Slowly, people start thinking they too should be getting big bucks like Mike, and disconnect their filter for $300 extra profit…

A self-interested person never has any incentive to use a filter. A self-interested person has some incentive to sign a pact to make everyone use a filter, but in many cases has a stronger incentive to wait for everyone else to sign such a pact but opt out himself. This can lead to an undesirable equilibrium in which no one will sign such a pact.

Alexander proceeds to list a range of examples of multipolar traps, some of which should now be familiar, e.g. capitalism, arms races and the state of the education system. He provides the following summary of the dynamic at play:

A basic principle unites all of the multipolar traps[…] In some competition optimizing for X, the opportunity arises to throw some other value under the bus for improved X. Those who take it prosper. Those who don’t take it die out. Eventually, everyone’s relative status is about the same as before, but everyone’s absolute status is worse than before. The process continues until all other values that can be traded off have been – in other words, until human ingenuity cannot possibly figure out a way to make things any worse.

We are manifesting a system where it befits us to throw wisdom under the bus, where if we do not sacrifice wisdom for short-term and narrow designs, we can’t compete and we will lose. Another way to think of multipolar traps is as “races to the bottom”:

Once one agent learns how to become more competitive by sacrificing a common value, all its competitors must also sacrifice that value or be outcompeted and replaced by the less scrupulous. Therefore, the system is likely to end up with everyone once again equally competitive, but the sacrificed value is gone forever. From a god’s-eye-view, the competitors know they will all be worse off if they defect, but from within the system, given insufficient coordination it’s impossible to avoid.

As such, given free reign, these traps have the potential to “destroy all human values.” We are clearly not at the bottom, and what is keeping us from the bottom is, according to Alexander, physical limitations, excess resources, utility maximization, and coordination. Limitations come into play as there are thresholds past which exploitative activities yield diminishing returns. As long as resources aren’t so scarce that we are locked in war, not all activities will be directed towards resource extraction. And in maximizing utility, there is luckily some semblance of ethical dimension to most human activities. Similarly, our activities are to some degree coordinated so as to lift us off the bottom, but the lack of global coordination and regulation ensures that multipolar traps will have the chance to arise whenever possible if there exists incentives for them.

Cognitive Traps and Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is defined as “the mental conflict that occurs when beliefs or assumptions are contradicted by new information.”8 Our beliefs and assumptions are a large part of our world views, and the disparity between our view of the world and new experiences is on the rationalistic model taken to be the error signal we use to update our world view to accord better with our experience.9 In reality, this “update” process is only one possible outcome, as we also employ other more defensive maneuvers, like “reject, explain away, or avoid the new information” or “persuade [our]selves that no conflict really exists”. In the words of Lubrano (2021): “People seek to resolve this, often excruciating, tension as quickly as possible, often unconsciously and usually in the easiest way they can.”

These mechanisms act as cognitive traps wherein we persist in a world view a part of us knows is wrong, and this contributes to not only “thinking traps” that are at work in anxiety disorders, like all-or-nothing thinking, overgeneralization and discounting the positive, but also political ideology, polarization and political disengagement. A reason for this is, as Lubrano notes, that cognitive dissonance occurs more strongly when it concerns an issue we feel responsibility for, or agency over. Thus, if we feel that we have little political agency, the cognitive trap is to disengage us from politics altogether, because this removes uncertainty and dissonance, while if we feel that we have agency and a responsibility, we often outsource this to “strong” leaders or ideologies, and we may excuse contradictory beliefs or behaviors on their part so as to minimize our own uncertainty and dissonance.

Limited Designs

Taking cognitive traps a step further, we may relate it to our designs, by which I mean our plans, goals, strategies, aims and so on. We base our designs on our world view, and because our world view is irreducibly limited, our designs will be too. This is of course nothing new, we always work on limited knowledge and “do our best” given the circumstances, but seen in conjunction with traps, both multipolar and cognitive, the effect on our limited world views and designs can be to both double down on them and update them in ways that serve motivations we are unaware of, even in the face of a contradictory reality.

Thus, in many cases we will persist in designs that do not internalize all externalities, designs that are quantity-based instead of quality-and-quantity-based, designs that are short-term and locally optimizing at the expense of the long-term and global context. There are obviously hard to predict and unpredictable externalities that arise from complex dynamics, and “unknown unknowns” that we simply will not be aware of until they actually arise, but using these as excuses are, as the Consilience Project observes, often used as a form of plausible deniability.10 Given what we do know and can predict, we still see a plethora of past and ongoing cases where we are aware of destructive side effects to our designs, but we persist in them anyway. Part of this is of course willful ignorance in service of egoism and self-protection, but the central reason is that we get caught in cognitive and multipolar traps.

The increased complexity of the multi-individual entities that arise as part of forming societies cut off inputs that do not short-term and locally benefit the higher-order entities constituted by the individuals. Such inputs may be ethics, long-term concerns, environmental concerns etc. Why are these cut off? Partly because they are not incentivized in the game-theoretic landscape of this higher-order organization, and partly because these entities are designed in limited ways that do not anticipate or internalize the full context of their organization. We are no longer solely bound by the evolutionary landscape sculpted by Nature, the conditions for our continued evolution are now also set by the landscapes of our cultures, economies and politics. These are in the domain of our designs, and whether we include in them considerations beyond the wealthy elite is our choice to make if any semblance of democracy is still at work. This is the reason why we need holistic design and regulation, in particular when it comes to the incentive structures we operate in. To an even greater extent this is why we need to cultivate values in ourselves and our children that allow us the wisdom to pass on opportunities to sacrifice our values, a topic to be returned to in the next essay.

Wicked Loops

The picture that emerges from this analysis is an interplay that create wicked loops made up of our world views, limited designs and cognitive and multipolar traps (Please excuse the simplistic figure):

There are erroneous elements in our world views, elements that pertain to our relationship to each other and reality. This dissonance pertains to our ontology and epistemology, our understanding of our ourselves, our experience and our knowledge of the world (as the first phase of this project has gone into detail about), and this dissonance lead us to create limited designs. These designs are short-term and narrow, not internalizing externalities. Cognitive traps reinforce our ignorance of these externalities, and thus our erroneous world views, due to cognitive dissonance. Multipolar traps also reinforce our limited world views and designs, and cause us to sacrifice our values in the pursuit of them. None of this is meant to excuse intentionally harmful behavior, but to provide a more nuanced take that supports the scope of our predicament, not all of which comes down to human wickedness.

These wicked loops are plural and at work at several levels of organization and human activity, and some act to reinforce each other. Thus there is a political trap of regulatory scarcity and incentive structures promoting short-term growthism, which drives economic-ecological multipolar traps of keeping up momentum at the expense of Nature, which drives cognitive dissonance and a trap of enforced ignorance and doubling down on erronous designs and beliefs. And of course, these traps act all ways, so that the cognitive dissonance and the trap of enforced ignorance where we throw out individual wisdom also drive the economic-ecological multipolar trap where we throw out collective wisdom, which further contributes to the political trap, and so on.

We may view in new light how technology, embedded in the wrong landscape of incentives, acts to skew our world views and our designs, and effectively trap us in relationships that are a detriment to ourselves and our environment. Technologies are extensions of ourselves, and a cognitive trap activates when contextual technological externalities cause dissonance. This trap causes us to either reinforce positive technological world views that ignore externalities and context, or to change our world views so as to minimize the dissonance, but often in the direction of more technology acceptance, even when the contextual motivator for the technology in question is solely growth-based. The Consilience Project (2024) classifies cases such as this as exemplifying Stockholm syndrome, where we through loyalty and sympathy in reaction to dissonance reinforce a world view where the true nature of our oppressor is hidden:

Those who clearly do not fairly or progressively benefit from our current form of progress but who still believe in it can be thought of as suffering from Stockholm syndrome. Effectively held captive by the current world system, sufferers respond with positive feelings toward (and a sense of shared identity with) the system itself, and these feelings are used to resolve the cognitive dissonance that arises as a result of the contradictions of their situation. We are “captive” in that we each have little personal control over the direction of the world, and we alter our perception of our captor by casting it in a more positive light. We may also observe the workings of the world and come to an understanding that there are two roles or scenarios open to us: that of the oppressor, or that of the oppressed. A psychological state that identifies with the role of the oppressor can seem preferable, because the belief that we are destined to be the oppressed forever is too painful to accept[…] it is far more comfortable to inhabit a worldview that suggests that the burdens of the present will be lighter in the future. The day-to-day experience of the oppressed is far less bearable—and we likely feel powerless to change it anyway.

As I mentioned at the outset, this world view-design-trap dynamic, these wicked loops, can only envelop part of the full reality that the metacrisis is. Numerous factors are at work in general, and many may be specific to a particular type of trap or area of society. A few of the contributing factors to the predicament are:

Jevon’s Paradox. Increased efficiency does not lead to decreasing consumption, but increasing consumption, due to the lowered cost that efficiency increase brings about. This rebound effect is partly responsible for how renewable energy has become an addition and not a replacement of fossil fuels, and explains how efficiency gains in production and manufacturing invariably leads to increased consumption and thus more extraction and production.

Incentive Structures, Coordination and Regulation. If a thing is incentivized or not disincentivized it will be sought out. Balanced incentive structures require coordination, but coordination is hard, especially when it is viewed as an enemy to profit. Regulation is notoriously lagging behind the activities of the market and innovation. Money corruptively binds the democratic power of regulation over perverse incentives.11

Physical limitations and game-theoretic factors. Resource scarcity/excess, demands, socioeconomic specifics and much more impact the interplay between our activities and our environment.

Cognitive Biases. A range of other cognitive biases contribute to distorting our world views and interpreting our experience and theories.

Narratives. Narratives overlay a constructed telos, a purpose, to the course of things, and these purposes often blind us to the costs of our advance in service of these purposes and stories.

As is clear, the metacrisis is highly complex, reflecting the complexity of our global form of society.

Complexity and Collapse

Tainter (1988) understands the collapse of societies as arising from their own complexity: the continued increase in sociopolitical complexity can no longer be maintained in the face of diminishing returns, and this makes excessively complex societies vulnerable. Sociopolitical structures require energy, and increased complexity in these structures generally require more energy. As with all processes of investment, the return on investment in complexity sees diminishing returns. This occurs due to extraction of the easy first (i.e. low-cost, low-labour, low-complexity) combined with increasing share of returns going back towards maintenance and existing complexity. As such, increased costs of sociopolitical evolution reach a point of diminishing marginal returns, making the society less resilient. This is inevitable given physical limitations. Tainter believes the only way out of this is a new, abundant source of energy that makes it possible to keep adding sociopolitical complexity. What a broader view affords us is that this on its own is not enough in a growth paradigm facing ecological destruction and planetary boundaries.

Ophuls (2012) has a similar point of view on the collapse of civilizations, seeing collapse as inevitable due the hubris of humanity, its immoderate greatness and failing to see its own flaws, and by extension the flaws of its systems. In addition to excessive complexity he identifies five other contributions to collapse: Ecological Exhaustion, Exponential Entropy, Expedited Entropy, Moral Decay and Practical Failure. He elegantly summarizes his own stance:

By way of summary, the complexity that is the essence of civilization is utterly dependent on a continuous input of physical, intellectual, and moral energy without which it simply cannot be sustained. But even this is not enough. In the end, to the extent that it can be done at all, managing a complex system requires prudence - that is, the exercise of judgment, caution, forethought, and self-restraint. Indeed, the real product of genuine systems analysis is not solutions but wisdom. To wit, understanding that excessive complexity is both costly and perilous and that management in the sense of control is unachievable. This would lead us to see that the proper (or only) way to "manage" civilization is by not allowing it to become too complex—in fact, deliberately designing in restraints, re-dundancy, and resiliency, even if the price is less power, freedom, efficiency, or profit than we might otherwise gain through greater complexity. To revert to our financial metaphor, to prevent busts, one must stop booms from happening in the first place by taking away the punchbowl of credit well before the party has gotten out of hand. So wisdom consists in consciously renouncing "immoderate greatness."

In light of this, it might very well be that a global society of humans is incapable of cohering for long, simply due to the complexities that are necessarily involved in its upkeep. This does not mean that we should not try our hand at finding new ways to organize ourselves, new forms of society, forms that de-complexify and simplify in an effort to build wisdom, resilience, balance and sustainability.

Excessive complexity and immoderate greatness can be seen as effects of wicked loops. Immoderate greatness is nothing but world view dissonance leading to designs of greatness that do not square with their costs and externalities, reinforced over time by cognitive traps. High-complexity organizational structures provide the space for more and new traps to arise. As society grows in complexity we historically see growth in technological innovation, and with this comes powers of extraction and expansion that require an inhibitory and regulatory force of equal power for their balance and wise application. Without the latter, multipolar traps will arise, and wicked loops are inevitable. This is not to say that the dynamic is not already in play in processes that counteract regulatory efforts.

I believe the world view-design-trap dynamic is, to echo Rowson’s description, essentially “within and between all the world’s major crises”. It can be applied to many of the facets of the metacrisis, and in doing so we can gain a vantage on our predicament as a whole that may afford us a world view from which we may both embed existing approaches and begin to chart out new approaches to how we deal with it. Escaping traps and approaches to dealing with the metacrisis will be the topic of the next essay.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this or any of my other essays, consider subscribing, sharing, leaving a like or a comment. This support is an essential and motivating factor for the continuance of the project.

References

Alexander, S. (2014). Meditations on Moloch. https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/07/30/meditations-on-moloch/

Borgmann, A. (1984). Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life: A Philosophical Inquiry. University of Chicago Press.

Encyclopedia Britannica (2024). Cognitive Dissonance. https://www.britannica.com/science/cognitive-dissonance

Hickel, J. (2020). Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. Windmill Books.

Hine, D. (2023). At Work in the Ruins: Finding Our Place in the Time of Science, Climate Change, Pandemics and All the Other Emergencies. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Lubrano, S. S. (2021). The Conundrum of Cognitive Dissonance: On the uneasy relationship between agency and understanding, and why it matters in Rowson & Pascal (2021).

Ophuls, W. (2012). Immoderate Greatness: Why Civilizations Fail. CreateSpace.

Rowson, J. & Pascal, L. (Ed.) (2021). Dispatches from a Time Between Worlds: Crisis and Emergency in Metamodernity. Perspectiva Press.

Stein, Z. (2021). Disarm the Pedagogical Weaponry: Make Education not Culture War in Rowson & Pascal (2021).

Tainter, J. A. (1988). The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press.

The Consilience Project (2022). Technology is Not Values Neutral: Ending the Reign of Nihilistic Design. https://consilienceproject.org/technology-is-not-values-neutral-ending-the-reign-of-nihilistic-design-2/

The Consilience Project (2024). Development in Progress: The concept of progress is at the heart of humanity’s story. https://consilienceproject.org/development-in-progress/

Hickel (2020).

The Consilience Project (2024), see the section “A High-Level List of Externalities of the Haber-Bosch Method”.

Stein (2021).

Hine (2023): “The crude choices offered at the ballot box encourage us to reduce politics to such us-and-them challenges. What goes missing is the possibility that we live in a time that is stalked by multiple dangers.”

See e.g. Borgmann (1984) or Don Ihde’s work, as summarized by Peter-Paul Verbeek: https://www.utwente.nl/en/psts/documents/ihde.pdf

The Consilience Project (2024), see the section “An Example of Maturity: Design and Use of Social Media”.

Jevon’s paradox also comes into play here, an important factor I will return to later in the essay.

Encyclopedia Britannica (2024).

See e.g. World, Model and Mind.

The Consilience Project (2024), see the section “The Threat From Progress”.

The Consilience Project (2024), see the section “The Law Is Failing To Bind Perverse Incentives”.

Nature has already figured out the solution to managing increasing complexity. Both multicellular organisms and brains do this. They form a new level of organization once the costs of managing complexity exceed the benefits due to synergy. Now, instead of having to deal with all the sub-parts, the new level only deals with parts. The sub-parts are hidden behind a level of abstraction (a membrane in a MCO and something else which we don't yet understand in a brain) and there is some subsidiarity at play, where the higher level lets its parts have autonomy over their sub-parts and does not micromanage the sub-parts. Successful companies within capitalism do this too, but there are issues with capitalism itself also destroying small companies in favor of large ones, and other intermediate levels between our individual brain modules and a nation-state (i.e. it destroys/outcompetes integrated individuals, families, tribes, villages and federations of tribes and villages). Molloch is a problem of insufficient intermediate levels from this perspective, and the solution is re-instatement of these levels.

Great breakdown Severin. I write a newsletter on the Metacrisis too and what you share aligns with most of my thinking. What pathways do you see out of the multipolar traps? I am on the hunt for a playbook for change!